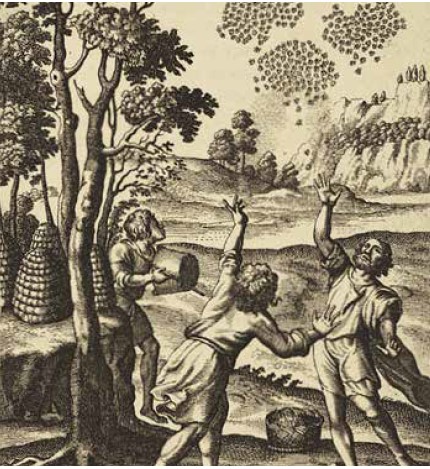

In April’s ‘Hive mind’, we asked if tanging, a traditional method of grounding a swarm, is still practised. Readers are responding.

Lucy Frost,

Medstead, Hampshire

To tang, or not to tang, that is the question! (Hive mind, April). Ho, ho, I hear you say, that sounds like an old wives’ tale. Well, I can assure you, I am an old wife, and it does work. Not every time, but in about a dozen attempts, it has been effective for me on six occasions. What a joy when it happens!

To tang, or not to tang, that is the question! (Hive mind, April). Ho, ho, I hear you say, that sounds like an old wives’ tale. Well, I can assure you, I am an old wife, and it does work. Not every time, but in about a dozen attempts, it has been effective for me on six occasions. What a joy when it happens!

The theory is that that the clattering you make interrupts the usual communication in a swarm – specifically, the bees cannot hear the queen piping, and this is what stimulates the swarm into action. Hence, when they can no longer hear her, they come together and fall down together, often on the grass. So, by placing your skep at an angle over them and gently smoking them, you can encourage them to move up into the skep.

There is a charming explanation of tanging in Curiosities of Beekeeping by LR Croft. He republished a letter to the Daily Mail in 1911 in which Betsy Powner, from Broseley in Shropshire, outlined her methods and reasoning. Ms Powner described herself as “an old countrywoman” with 60 years’ knowledge and love of bees. She wrote that the aim of tanging bees was “to drown the voice of their young queen and leader” with “rough music” made with a door key and a warming pan. In that way the swarming process would be disrupted.

I decided to try it. My tools are only a little more recent – a grooved rod and doublehandled small copper pan.

My most spectacular success was when I was having a cup of tea with the family prior to collecting the swarm, which was conveniently hanging five feet up on a nearby apple tree. It started to move off and I explained I had to move too – fast. After about three minutes of clattering, down came the swarm, and I housed it just as I have described. Wonderful!

I don’t know why tanging should be effective sometimes but not others. However, I have noticed that if I start the very instant the swarm begins to emerge from the hive – or to move off if it has already settled – this appears to be when the bees become most disconcerted and it works. The louder the tanging the better – and it must be metal on metal. I continue for at least ten minutes with no breaks to have any hope of success. It’s quite exhausting. If the aerial ballet of the swarm is well under way, it is much harder to persuade them to abandon it but, even then, sometimes I have been lucky if I persist for ten minutes or more.

In another incident recently, the bees collapsed/descended on me! They formed a very cosy and warm extra jacket on my beesuit and did not feel like a threat at all. Luckily, I had my phone (my husband would probably have passed out had I needed to return to the house to pick it up), so I called a colleague from the other side of the village to come and brush the swarm down into a skep. (She took the photos.) I did consider standing over a skep and jumping to release the bees, but I thought that might have unforeseen consequences.

Now I take the equipment with me every time I go to a swarm. Since my pan is made of copper, it is becoming quite dented. Happy tanging!

Croft, LR (1990). Curiosities of Beekeeping Northern Bee Books.

Dorian Pritchard

Hedon-on-the-Wall, Northumberland

Yes, BeeCraft, some of us yokels still practise tanging. I taught my non-beekeeping wife to do it in case a swarm appears while I’m away. She’ll “wake a dong, and clash the cymbals of the dame”, as Virgil advised 2,000 years ago.

We find it works most reliably when the bees are in an undecided state, waiting for a directive, less so when they have started flying with intent. In the latter case they may settle temporarily, but can up and depart again half an hour later, or after you’ve collected them in a skep but haven’t yet housed them.

I once timed how long it took for the swarm to cluster. Almost immediately after I had begun my action, they began to collect on a prominent branch and in about five minutes a sizeable cluster had assembled. That evening I housed them in a wooden hive and they settled down well. That is not always the case, but once they’ve produced wax, that usually signifies they are there to stay.

So it definitely works – sometimes. We tend to use a Texan copper cowbell or a wooden spoon and a cheap tin tray. I have not previously heard of using a door key.

Tanging history

The story goes that tanging dates back to the birth of Zeus. If you calculate it in relation to the reigns of the kings of Crete, it leads you to the end of the Copper Age (the transition between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age), which would make it roughly contemporary with Ötzi, the Ice Man, who, you may remember, had a copper axe head among his possessions. Zeus’s father, Chronos, practised a form of family planning of which most of us these days would disapprove. It involved cooking and eating the babies his wife produced, soon after birth. In order to remove baby Zeus from the menu, she spirited him away to a cave (which I believe you can still visit) at the other end of the island. There he was placed in the care of two young ladies, one a beekeeper called Melissa and the other a goatherd.

The story goes that tanging dates back to the birth of Zeus. If you calculate it in relation to the reigns of the kings of Crete, it leads you to the end of the Copper Age (the transition between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age), which would make it roughly contemporary with Ötzi, the Ice Man, who, you may remember, had a copper axe head among his possessions. Zeus’s father, Chronos, practised a form of family planning of which most of us these days would disapprove. It involved cooking and eating the babies his wife produced, soon after birth. In order to remove baby Zeus from the menu, she spirited him away to a cave (which I believe you can still visit) at the other end of the island. There he was placed in the care of two young ladies, one a beekeeper called Melissa and the other a goatherd.

To put her husband off the track, Zeus’s mother told him she had killed the baby, and handed him a bundle, which actually contained rounded stones.

I’m sure the young ladies had great fun looking after little Zeus, except that he sometimes cried a lot and they feared someone would hear him and report back. So they got into the habit of dancing whenever Zeus cried loudly, and making a lot of noise by clashing their weapons together. It is said that on one occasion Melissa’s bees started to swarm at the same time as Zeus was wailing and she noticed that when they clashed weapons the swarm settled. And we have remembered the event ever since. Interestingly it could not have happened before the Copper Age, as there was no pure metal in existence then to create such a noise.

So it works with the bees of ancient Crete (Apis mellifera adami), with Virgil’s in Italy (A. m. ligustica), and with our A. m. mellifera in Northumberland. This behavioural response by the bees could therefore be millions of years old, arising before those races went their separate ways.

A bee ear

Bees do have a type of ear and like ours they contain minute, sensitive hair-like structures that flex in response to sound. They are situated within the bend near the base of each antenna, in what is called Johnston’s organ and are said to be particularly important for interpreting the audible components of the waggle dance. It has been suggested the clashing sound is interpreted as thunder, a fairly reliable predictor of torrential rain, and they settle down rapidly to avoid getting too wet.

Colin David

Tandridge, Surrey

A broken old metal watering can lives in the corner of my apiary for tanging. The broken-off spout is the baton used to bang the watering can.

I would like to say that it is used to encourage passing swarms to settle, but I have to confess it’s used to try to retain swarms from my own apiary – no swarm control method is 100% effective!

The tanging works well. An emerging swarm has always settled in the apiary when I have banged the can. There is no saying whether or not the swarm would have settled close by in any event. Sadly, I have never brought down a passing swarm.

A dustbin lid and stick are also effective, but there is nothing quite like metal on metal for the perfectly pitched racket.

Fortunately, I have no near neighbours, so I can tang away to my heart’s content when necessary.

A bait hive works well too.

May 2021

Subscribe to BeeCraft Magazine

- £27.00* - Digital Subscription | 12 months

- £45.00* - UK Printed Subscription | 12 months

- £80.00 - UK Printed Subscription | 24 months

* UK residents over the age of 18 can subscribe to BeeCraft via Direct Debit and save up to £7.00 on your subscription. For more information on our Direct Debit scheme, please click here.

- £27.00 - Digital Subscription | 12 months

- £50.00 - Digital Subscription | 24 months

- £67.00 - RoI & European Printed Subscription | 12 months

- £27.00 - Digital Subscription | 12 months

- £50.00 - Digital Subscription | 24 months

- £90.00 - Worldwide Printed Subscription | 12 months